Salary Negotiation

Salary negotiations can be the trickiest area to navigate within a job application or selection process, requiring preparation, confidence, sometimes 'nerves of steel', and a clear understanding of your worth. The following advice is validated through over a quarter of a century advising and coaching hundreds, if not thousands, of individuals before, during, and after their salary negotiations.

Preparation is Key

Research: Know the market rate for your position by using online resources like Glassdoor, Payscale, or LinkedIn's Salary Insights. Additionally, many recruitment companies compile excellent salary guides so you should check those out too.

Track Your Achievements: Keep a record of your accomplishments and contributions to the company. This will help you make a strong case for your worth.

Know Your Worth: Make a list of your skills, qualifications, and experience. Be honest about your strengths and areas for improvement.

The Art of the Ask

Timing is Everything: Schedule a meeting with your supervisor when they're likely to be available and not too busy or distracted. For job candidates, time negotiations so they occurs after you've made your strongest case , is a desirable outcome.

Be Confident but Not Arrogant: Approach the conversation with confidence in your abilities, but avoid coming across as arrogant or entitled.

Use "I" Statements: Instead of saying "you should pay me more," say "based on my research and achievements, I believe my salary should be adjusted to reflect my value to the company."

Be Specific about What You're Asking For: Clearly state what you're asking for in terms of a salary or other benefits.

Example: "Based on my research, I believe my salary should reflect industry standards. I'm respectfully proposing a 10-15% increase above what you're offering."

Be Prepared to Negotiate: Your supervisor may not be able to grant your request immediately. Be prepared to negotiate and find common ground.

Look for Creative Solutions: If the company can't offer a salary increase, explore other benefits like additional vacation time, flexible work arrangements, or professional development opportunities.

Salary negotiations for a new job involve different principles when it comes to counteroffers. If you're in a job and negotiating salary at another company, be prepared for a counteroffer from your current employer once they get wind of your situation.

For these counteroffers be aware also that if it's just more money then most people leave after 6 months anyway because leaving a job is usually more than disatisfaction with remuneration

For those not currently employed it's advised to generate multiple job offers and leverage all salaries and employment conditions presented, for the role and company that is your preferred option.

Counteroffers & Compromise

Cognitive Bias in Negotiations

The brain uses heuristics or rules which help thinking to run efficiently and allow us to work sucessfully with complex +information as well as navigating interpersonal dynamics like relationships with other people. As a result some of these rules can become biases in our thinking - making us deviate from good thinking and decision making to a less optimal approach.

Nobel Prize Winner Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, the early pioneers of cognitive bias research, and whose work would later launch the broader area of behavioural economics, developed the concept of Prospect Theory which argues that people make decisions based on potential gains and losses rather than absolute values. This theory has been widely applied to negotiations. They showed that people tend to fear losses more than they value equivalent gains. In negotiations, this means that we might be more motivated in general to avoid concessions than we are to pursue them.

In addition to loss aversion, within their theoretical framework Kahneman and Tversky initially outlined three principle biases: availability, representativeness and anchoring biases. Two of these original cognitive biases (as well as a number of later-defined biases listed below), can have a significant impact during salary negotiations), so being aware of their impact and influence during negotiations, and equally importantly having some mitigating strategies, is advisable.

Anchoring Effect: The initial offer or anchor can significantly influence our perception of subsequent offers. This bias leads us to rely too heavily on the first piece of information, often resulting in poor decisions.

Specifically, this bias - also called anchoring and adjustment - acts so whatever figure is first put out there during a negotiation becomes the anchor point, and any subsequesnt negotiation may adjust around that point but not by a huge amount. Meaning an employer is incentivised to go in the lower range with an offer and the employee is incenivised to go in the higher range.

Framing Effect: The way information is presented (frame) can impact our decision-making. For example, a positive frame might lead to more concessions, while a negative frame could result in less willingness to compromise. Framing is really active, and powerful, right at the start of a negotiation and sets the tone for much, and sometimes all (in the case of highly positive or negative framing effects), of the salary negotiation process.

A positive frame might be conveyed through the following employee statement: "Look, salary is important as I expect to be fairly rewarded for my skills and effort, however the opportunity to work with highly skilled people who share similar values and do work that is meaningful in the world, is also a significant part of my motivation, so hopefully salary doesn't become a sticking point". Here you have: not conceded any ground by revealing a figure; underlined fairness and goodwill; and framed things positively by emphasising the quality of people at the company and the nature of the work they do as well as your collaborative preference and alignment with values.

Sunk Cost Fallacy: We tend to overvalue investments we've already made due to the sunk cost fallacy. In negotiations, this means that we might be reluctant to abandon a suboptimal agreement due to fear of "wasting" resources. Simply put, we become entrenched in a salary negotiation that drags on and after time calculate that 'walking out the door' now would be a big loss (when really it's only a few days but we maximise this value in our minds thinking we've invested a lot of 'sweat equity' in the negotiation).

Now while this might be so, also remember that we need a big picture perspective as well - calculating not the cost of time already invested (sunk cost fallacy), but the real cost of things such as lost future salary (e.g. if you were to start getting paid next week/month), the opportunity cost of any associated benefits requiring a guarantee of regular income through employmnet, like a business loan, line of credit, or mortgage - not to mention, the opportunity to be promoted or earn salary bonuses sooner through strong performance.

Confirmation Bias: Our tendency to selectively seek information that confirms our initial beliefs can lead us astray in negotiations. We might ignore or discount opposing views and facts. This is a variation on the stereotyping process where we tend to minimise information which is inconsistent with our viewpoint and pay more attention to information, ideas, values etc. which are in line with our own baseline for these.

In a salary negotiation for example, we as an employee might attribute more weight to the experience we have, in determining our relative position on a salary range, but the organisation with which we are negotiating may feel that knowledge of current technologies like AI, or competencies like business strategy, demonstrated teamwork & collaboration, or leadership, might be more important in deriving a fair salary offer for you.

Hindsight Bias: The tendency to believe, after an event has occurred, that we would have predicted it is a cognitive bias. In negotiations, this means that we might be overly optimistic about the outcome or underestimate potential risks. Unlike its folk psychology counterpart, this bias does not have 20/20 vision.

Rather, like with confirmation bias, we fail to see things that are outside our perspective, but additionally with this bias we later think they were in our perspective. In this way we fail to learn from mistakes or make course corrections, during extended salary negotiations or in future negotiations.

Availability Heuristic: Our perception of the importance or likelihood of something is influenced by how easily examples come to mind. In negotiations this might manifest simply responding to a question about previous earnings, where you recall only last year's salary which may not be truly representative of the overall value and contributions made in your last role.

This bias can also lead us to overemphasize dramatic or vivid scenarios (additional saliency effect) while underestimating more common outcomes. This is also why during a job interview one of the reasons it's recommended to prepare question responses beforehand, especially weaknesses, fails or mistakes, is to avoid falling into a variation of this bias, whereby you providw an example off the top of your head which might not be a good example - just easy to recall in memory.

Simpson's Paradox: When we analyze data separately for each subgroup, but aggregate results show a different trend, Simpson's paradox occurs. This is not really a paradox but a bias which can lead us to misinterpret patterns in information, including during negotiations. It's a pretty complicated one to explain but might be described as a type of pop-science / pop-psychology error, whereby a hidden or unknown factor is really contributing to the apparent relationship between two other factors or variables but we don't know this.

For example, most people might not know that there's a range of pretty strong relationships between our social media digital footprint - what we endorse or dislike online - and our personality, how people describe us, and other characteristics. So, we might assume that there is a factor or factors influencing how we are being treated in a negotiation, but the company through their social media profiling of you have reached a different conclusion based on their algorithms.

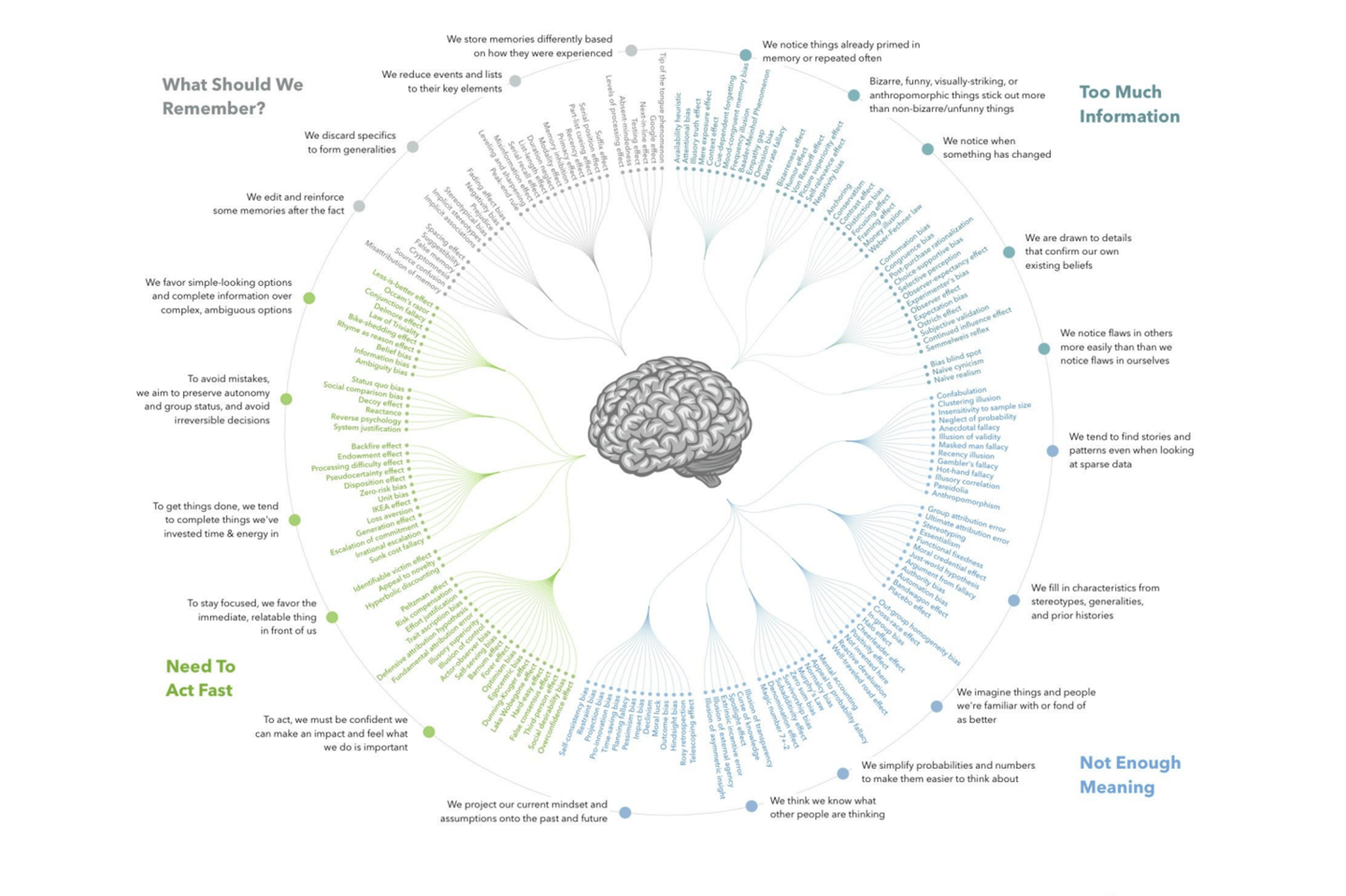

The initial single to double-digit biases originally proposed by Kahneman & Tversky have now grown to hundreds. The graphic below provides a comprehensive overview of these biases, along with their underlying rules and heuristics, and was created by John Manoogian III and Buster Benson, who compiled the list of biases from Wikipedia.

Cognitive Bias Codex

Review Career AI Salary

To receive tailored feedback on your salary or for recent jobs you've worked, subscribe to Career AI. You can also use content from your CV to justify higher pay as well as getting tips on what changes you can make to your CV to improve your salary negotiating position. Upload your Career Development Report (sold separately) to get insight into your negotiating style and how you can leverage this during salary negotiations. More details in the link below.